In his recent book, The Strength of Paradise, Jonathan Holslag indicates work has become trivial and unattractive for many people in modern societies (1). He argues for a stronger focus on values that are essential to human existence and contends that values such as meaning, recognition, and security can be met in the workplace. In addition, we propose that if such values actually materialize in the work setting, people are more likely to be capable and willing to continue to work. In other words, they will be more sustainably employable. If this notion is correct, it would become important for professionals in the field of work and health to pay greater attention to such value dimensions of work. In this paper, we propose a conceptual model of how resources, context, sustainable employability, and values might be related. This model is based on the concept of capability, as developed by Amartya Sen (2–4). Briefly, this model holds that an individual’s sustainable employability is determined by how he or she succeeds in converting resources into capabilities, and subsequently into work functioning, in such a way that values such as security, recognition and meaning are met. In this paper, we elaborate on the nature of these resources and conversion factors. We also explore how the different elements of this model relate to existing concepts in the field of occupational health such as employability, the framework of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) (5), and psychological models of work and stress. We provide a research agenda for testing, validation, and operationalization, as well as discussing implications for practice. In an accompanying paper also published in this issue, we report on the development and validation of a questionnaire that allows for the assessment of sustainable employability, based on the concept of capability (6).

Our model aims to encompass the complexity of contemporary work, especially the value-related aspects of work. For present-day workers in the Western world, work is a life domain in which they want to achieve important goals and values, in addition to income security. Work should offer the opportunities to actually achieve those goals and values.

Participating in work is important from both a societal and a personal perspective. On a societal level, in all European countries, greater and prolonged labor-force participation throughout a worker’s life is necessary in order to confront the social and economic realities and challenges of an aging society. Workers will need to work until an older age, and those with disabilities will need to be integrated or reintegrated into the workforce (7–10).

On a personal level, earning a living has been the most important work-related value throughout history, and only recently, in the post-industrial economy, have other values connected to work become attainable for a considerable number of workers. For Jahoda, income remains the central value; however, she stresses the importance of other work-related values, which she calls “latent benefits”, such as personal identity, self-esteem, and social contacts (11). Hannah Arendt formulates three central work values, resembling those of Aristotle, of which a person’s livelihood (labor) is one. The other two values are creativity (work) and participation (action) (12). In our own research, reported elsewhere in this issue, we identified seven values or work capabilities, of which income is one (6). Thus, for workers in the post-industrial economy, although demanding, work is also an important domain of life in which ambitions and values can be realized (13–15). Moreover, work can contribute to health, if basic conditions and values are met (16, 17).

In summary, work is an important means of achieving societal and personal goals and values, of which generating income is only one, albeit an important one. In developed economies, employment – including self-employment – is one important way in which work is embedded in society. A person’s ability to gain and maintain employment is referred to as his or her “employability” (18). As argued above, present-day workers require a wider range of valued outcomes from their work than an income alone. For these workers, work – and in line with that, employment and employability – is sustainable if it can provide those broader values. We use the term “sustainable employability” to incorporate a focus on values in the concept of employability. In the following sections, we will introduce a framework, based on the CA, in which an emphasis on values is added to notions of work and employability. To put our framework into perspective, we will first briefly discuss recent changes in theories of work, health and employability.

The changing world of work, health, & employability

Our conceptualization and appreciation of health and work are changing rapidly. The World Health Organization’s (WHO) 1948 definition of health (19) points towards an almost unattainable spot on the horizon: a static state of optimal physical, mental, and social well-being, which as a goal, especially as a sustainable one, cannot be obtained. In the ICF, the WHO no longer gives health the position of a final outcome but rather describes it as a determinant or an input for participation (5). In recent descriptions, health is viewed as a capability (20), a process of constant adaptation (21), or a meta-capability: a condition necessary in order to enable people to accomplish valuable goals in their lives (22). Thus, in just a few decades, ideas concerning the role of health have changed dramatically: from output to input, from state to process, and from target to agent.

The centrality of work in people’s lives has also changed considerably with the transition from industrial to post-industrial labor (7, 23–25). In the middle of the twentieth century, the vast majority of Western European workers were employed in an industrial or an agricultural setting. They were primarily exposed to tasks of a limited complexity involving a mainly physical workload, within a relatively stable work setting. Lifelong employment was often the norm, sometimes in health-threatening work conditions. Work was seen as a necessary evil, as a means of providing a livelihood, and often posed a health risk (26). In contrast, nowadays, the majority of workers in the Western world are employed in the service sector (particularly in healthcare, education, tourism, the financial sector, and ICT). In these professions, physical working conditions are generally not threatening to physical health, but the work can be complex and demanding. However, these demands are predominantly mental and emotional in nature, involving risks to mental rather than physical health (27). Work is now typically performed in a dynamic context (in which temporary contracts and changing teams are common) characterized by shared decision-making. Workers continually interact with clients or customers, requiring flexibility and communication skills. Moreover, ongoing technological developments have changed the nature of the work carried out (28).

In this process, the average worker has developed from a more-or-less passive performer of predefined tasks to an increasingly autonomous and responsible entrepreneur in his or her work (“intrapreneur”) (29), who proactively sets his/her own goals and makes his/her own choices and (shared) decisions (27). For many people, work is now a life domain in which they can fulfill their ambitions and achieve important goals. Meanwhile, health has become a condition or resource that enables workers to carry out their work.

Thus, work and health have changed places. In the past, work was the determinant and health was a state that people strove to maintain despite the burden of work. Nowadays, health is the resource, and employment or work is the state that people want to preserve, sometimes despite the burden of suboptimal health. This has implications for the field of occupational health, an important goal of which is to influence the work situation in order to optimize health. In view of the changing and dynamic conception of health – in which health, on the one hand, should enable people to pursue and achieve valuable goals and, on the other hand, will be positively influenced by that process – it is important that the role of the occupational health worker reflects these changes. This role should now include advising workers and their organizations how important values can be met and goals achieved. This will in turn contribute to health and sustainability and to an individual’s choice and ability to take later retirement. This counts for all workers; particularly for specific subgroups of the labor market – predominantly precarious (often low-skilled) workers – for whom, notwithstanding the trends depicted above, there is a tendency towards a deterioration in working conditions, especially since the start of the economic crisis (30–33).

In summary, values constitute an important aspect of work, and by extension, of employment and employability.

Most definitions of employability stress the individual aspects of the concept (18, 34–36). Gazier, following a thorough description of the trends over time in conceptualizing employability (37), identified seven trends or phases, five of which focus on the individual. The trends evolve from stressing moral characteristics (undeserved or deserved employability or unemployability), via sociomedical aspects (social, physical, or mental factors) and competencies (knowledge, skills, and attitude) to self-direction, where the emphasis is firmly on the person’s initiative and agency.

A different approach emerged in France in the 1960s, focusing primarily on the demand side and the accessibility of employment, with employability defined as “the objective expectation, or more or less high probability, that a person looking for a job can have of finding one” [Ledrut, quoted in Gazier (p44, 37)].

Another trend, identified by Gazier and which emerged in the 1970s, focuses on measurable labor market outcomes, such as the period of time an individual is employed, hours worked, and wage rates that result from specific policy interventions. Finally, the notion of interactive employability has been put forward, whereby employers and policy-makers interact with individuals in order to gain and maintain employment. While accepting the importance of individual agency, this notion sought to balance personal efforts with structural factors (37).

If, in this last and most recent notion of employability, workers and the work environment strive to gain and maintain employment in work that is valuable for the worker and valued by the work context, then, in our view, work, and – by extension – employability, can be seen as sustainable.

The capability approach

The capability approach (CA), introduced by Amartya Sen (2–4), offers a framework in which an emphasis on values can be added to work and employability. The CA states that individuals should have the capabilities to conceive, pursue, and revise their life plans (22, 38–43). There are three important elements in the capability approach, namely capabilities, functionings – in which values are emphasized – and freedom. In the most basic sense, functionings represent the states and activities that constitute a person’s being: “beings and doings people have reason to value” (p40, 44). The capabilities of an individual reflect the different combination of functionings that person is able to achieve, depending on his/her particular circumstances; the various combinations of what s/he can do or be. According to Sen, an individual’s well-being should be assessed in terms of capabilities, since functionings may be the result of constrained choices or reflect a limitation in choices. In order to understand the individual’s situation and develop useful interventions, it is important to evaluate what an individual can do or is able to do, and not just assess what he/she actually does.

According to Sen, freedom is, on the one hand, the possibility to shape one’s life and living environment (process) and, on the other hand, the possibility to achieve valued goals (opportunity) (4). He equates capabilities with freedoms; capabilities reflect the freedom of individuals to do what they wish to do and to be what they want to be (38). Capabilities therefore represent a person’s opportunity and ability to achieve valuable outcomes, taking into account relevant personal characteristics and external factors: being able and enabled. Applied to work, this ensures valuable work outcomes, which in our view is an important aspect of SE.

Alkire (45) illustrated the richness of the capability concept with a simple example regarding cycling. If someone has the physical properties and the skills essential for cycling, s/he can cycle (s/he has the capacity). However, if s/he does not possess or cannot make use of a bicycle then s/he cannot cycle. Similarly, if there are no roads that are suitable for cycling, s/he cannot cycle. If there is a curfew in effect, s/he cannot cycle either. Capability includes all these diverse aspects: personal resources (the physical properties and skills required to cycle), material resources [ownership of (or access to) a bike], and the physical (appropriate route) and social (no curfew) environment. These aspects together determine whether personal and environmental resources and characteristics can actually be exploited to realize the “functioning” of cycling (with, as a starting point, the assumption that this is a valuable functioning in the circumstances). The crux of the capability concept lies in the combination of various meanings of “can”, which refer to: (i) being able to; (ii) having opportunities; and (iii) being facilitated and allowed. In fact, (i) refers to what a person can do, whereas (ii) and (iii) refer to the interaction with the context that enables the person to use his or her resources and capacities and realize opportunities. The CA differs from resource models or utilitarianism, in that possession of a bike or the ability to cycle are only important to the extent that they allow a person to cycle, if relevant. Welch Saleeby (46) provides an example of two individuals who own bicycles. Individual A does not use the bicycle although s/he knows how to; s/he can actually ride the bicycle, but with regard to mobility and transportation, prefers to drive. This differs from individual B, who does not use the bicycle because s/he has never been instructed on the use of this specific bike, his/her parents restricted bicycle usage, or because s/he cannot manipulate the pedals due to a mobility limitation or impairment. For this person, notwithstanding the possession of a bike and the general ability to cycle, biking is not a “capability”.

As with cycling, in work, all these different aspects of capability – from identifying a valued functioning to being able and enabled – are crucial. In other words, the individual worker must be both able and motivated to work. Moreover, the context in which the work is performed must enable the execution of valued tasks, contributing to goals that are personally significant and valued by the organization.

Definition and a model of sustainable employability from a CA perspective

Based on these considerations we formulated the following definition: sustainable employability means that, throughout their working lives, workers can achieve tangible opportunities in the form of a set of capabilities. They also enjoy the necessary conditions that allow them to make a valuable contribution through their work, now and in the future, while safeguarding their health and welfare. This requires, on the one hand, a work context that facilitates this for them and on the other, the attitude and motivation to exploit these opportunities (47).

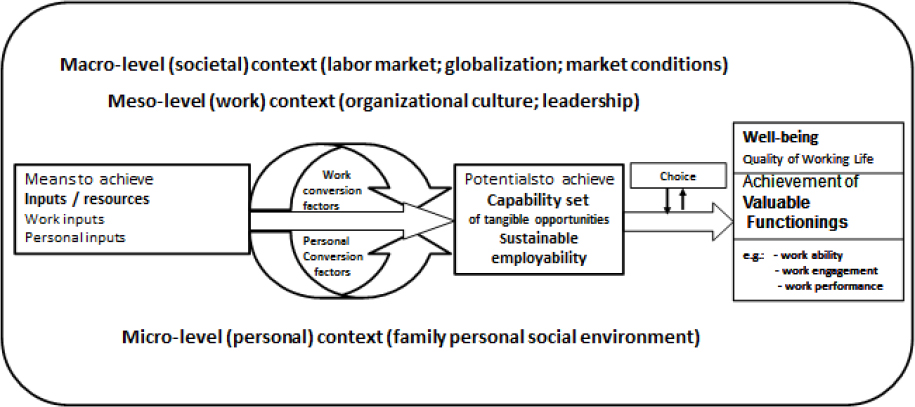

Central to this definition is a set of tangible opportunities (capabilities) for achieving and maintaining valuable functioning at work (ie, employment in valuable work). It is essential that there are personal and environmental (work) conditions which enable workers to convert personal input and work input into these capabilities (real opportunities for valuable work functioning). In line with this definition, we have developed a model of sustainable employability (figure 1), in which the notion of a capability set plays a crucial role. The model (especially the central line in the model, from inputs on the left side to functionings on the right side) is derived from models by Sen, Robeyns, Morris, and Welch Saleeby (41, 46, 48, 49) and applied to sustainabile employability.

The model represents the process whereby an individual worker in his/her context can convert inputs or resources into opportunities to make choices to achieve valuable goals.

At the center of the model is the capability set: the set of tangible opportunities that can be used to achieve various valuable functionings. This set, in our view, represents the best possible operationalization of sustainabile employability. An example of a valuable work functioning, important for many workers and one of the seven work values we identified in our research, is the opportunity to develop knowledge and skills. This value can be considered to be a (work) capability for a person if: (i) it is an important value for this person in his/her particular work situation; (ii) s/he is enabled by the work context (eg, challenging tasks and an adequate HRM policy); and (iii) s/he is able to achieve it (eg, the ability to learn). This combination of experiencing a value, being enabled, and being able, by means of both inputs and conversion factors (see below), constitutes a (work) capability.

On the left side of the model, personal and work inputs or resources at the worker’s disposal are depicted. On the personal level, this refers to personal capacity; on the work level, this embraces work characteristics such as task structure and work demands. In our example of the opportunity to develop knowledge and skills, the personal resources that a worker can draw upon include his/her knowledge and ability to learn. Of course, other more general inputs and resources are important too, such as health, education, and general competency and abilities. Relevant workplace inputs and resources, in our example, include a diversity of tasks involving different levels of required skills and complexity, which constitute a learning environment.

Between inputs and capabilities, the so-called “conversion factors” play an important role. In order to reach their goals, workers should not only be able to draw upon inputs but they should also be able to convert those inputs into tangible opportunities in order to achieve valuable work-related goals. Returning to the example of the two individuals owning a bike, individual B possesses a bike (the resource) but experiences negative “conversion factors” that prevent her/him from using the bike. In our example of developing knowledge and skills, relevant conversion factors include the attitude and motivation to learn and acquire new skills on the personal level, coupled with an HRM policy of employee development on the organizational level. Thus, in our model, work inputs and personal inputs are not mere determinants of sustainabile employability in the classical sense, but they are factors that can lead to a set of potentials (the capability set) to achieve valuable work functioning, provided that appropriate personal and contextual conversion factors are present.

On the right side of the model, the actual (work) functioning of the worker is depicted – the valuable functionings that s/he chooses to achieve from his/her wider capability set. This achievement is the outcome of choice on the part of the worker along with his or her work context. The environment plays an integral role in determining the achievement of functionings by influencing aspects such as choice, preference, and importance. Sen speaks of “constrained choice” when external forces (eg, social forces like stigma or attitudes) constrain personal choice. Exactly because of this, the CA emphasizes the need to move beyond what individuals are doing, which might be influenced by constrained choice, to assessing what individuals are able to do or to be – their individual capabilities.

Well-being, in this case quality of working life, is also depicted on the right side of the model. Well-being is not only related to what an individual achieves, but also to the options which he/she has had the opportunity to choose from. This element is also regarded as a less important proxy for sustainable employability than the capability set because the perception of a situation can be subject to a “response shift”, that is an adaptation of norms to the prevailing situation, while capabilities represent factual opportunities and freedoms.

Contextual factors are important because they can influence inputs, conversion factors, and decisions or choice, according to which capabilities are achieved in actual work functionings.

The complementary value of the CA to models of work and health

Although the primary focus of the ICF was on disability, the WHO has positioned it as a universal framework of health and its related states (50). Due to its focus on functioning, the ICF is also widely used in occupational health. It is a diagnostic framework designed for classification purposes and not a conceptual model aimed at understanding aspects of reality. As such, the two systems (ICF and CA) are complementary to each other. In a thorough discussion of the parallels between the CA and the ICF, Welch Saleeby advocates using the ICF classification scheme to operationalize the capability theoretical framework (46). The CA adds the elements of value, opportunity of functioning, freedom, and choice to the ICF.

Psychological models of work and health focusing on work stress have been developed since the 1960s. The Michigan Stress Model (51) identified workload, job control, and social support as unidimensional determinants of work stress. In the next phase, balance models were developed. Karasek developed a two-dimensional model that assumed that job control, the freedom that workers have to make choices in their work, may balance the stress of high work demands and can even lead to a situation in which demanding work is challenging, as in a learning environment (52). Other models focus on the importance of a good fit between person and environment (PE-Fit) and, more specifically, between person and job (Person-Job-Fit model (53, 54). In some models, a specific aspect of this balance is emphasized, for example in the Effort–Reward Balance model (55, 56). The Job Demands Resources (JD-R) model (57) can be seen as a broadening of the Karasek model in the sense that it extends to all types of resources that an individual can have (instead of just job control, which is actually more a job characteristic than a resource) and emphasizes the energizing and motivational aspects that work may have if relevant resources or characteristics are present.

Importantly, by considering both value and context, the CA can add to and extend existing models that have been developed over the past decades and are undoubtedly valuable in identifying sources of stress. A good balance is still relevant and necessary, and contributes to sustainable employability (58). However, for modern workers, it is not sufficient to have just a good balance between demands and resources, demands and abilities, or efforts and rewards; they also need to have a good fit or balance with regard to what they consider to be important values in their work. For sustainable employability, in the current work setting, it is crucial that workers are able and enabled to attain significant goals in their work, which are concordant with their core values. The concept of value adds to existing models by providing direction to (and within) the balance and fit models: what aspects of a fit are important? What goal is the motivation aimed at? What resources are needed, and what aspects of work are rewarding and contribute positively to the effort–reward balance of a worker? Most elements of the psychological models can be easily integrated into our model of sustainable employability, either as inputs or as conversion factors.

Research agenda and implications for science and practice

Having proposed a definition and a model – the focus of this article – the next steps should be to test the validity of the model and the assumptions underlying it. Part of this has already been done and is reported separately in this issue (6).

The first step of a research agenda is to operationalize the core elements of the model. In our model, instruments are needed to identify whether an individual has a capability set that allows him/her to achieve valuable work functionings. To this end, we developed a new instrument based on our model. The core and most innovative part of this instrument is a set of capability questions [questionnaire and its validation (6)]. In order to identify relevant capabilities, we used a mixed method approach. The core of this approach was to conduct qualitative interviews so that we could ascertain exactly what workers value in their work. We identified seven work values: (i) the use of knowledge and skills, (ii) the development of knowledge and skills; (iii) involvement in important decisions; (iv) building and maintaining meaningful contacts at work; (v) setting own goals; (vi) having a good income; and (vii) contributing to something valuable.

In our assessment, we kept close to the basic idea of the capability concept by asking, in relation to each of the seven values: (i) “How important is <the value> for you?”, (ii) “Does your work offer you the opportunities to achieve <the value>?” (iii) “To what extent do you actually realize <the value>?”.

We determined whether each value comprises part of a worker’s capability set (ie, whether it is considered to be valuable in the specific situation, is enabled in the work context, and can be realized).

The other, individual and contextual, aspects of the model presented in figure 1 are covered partly by existing and partly by newly developed scales.

The next steps in our research agenda are: (i) further validating our instrument: test–retest reliability and construct validation in longitudinal designs; (ii) model testing: testing the relationships between different elements of the model, preferably in longitudinal designs, particularly the complex and reciprocal relationship between functionings / capabilities on the one hand, and health on the other; (iii) testing the validity of the model and the instrument in specific groups: transcultural validation; age, education or gender differences; (specific) chronic diseases; et cetera; and (iii) developing and evaluating interventions derived from the core principles of the model: strengthening the capability set, optimizing resources, conversion factors and freedom to choose actual functionings.

Our major thesis in this paper is that people are more likely to be sustainably employable if their work does not merely represent a means to earn a living but if it can also be demonstrated to be intrinsically valuable. This requires value deliberation at the workplace. The model shifts the focus from subjective well-being to what workers are objectively capable of, and from actual performance to the range of valued functionings that a worker can achieve. Moreover, it shifts the focus from resources alone to an emphasis on resources and conversion factors. Each of these notions needs to be specified further with regard to the work context, which will involve both theoretical and practical challenges. These will need to look beyond economic factors when assessing work and evaluating policy and interventions. This implies that other evaluation criteria should be developed.

On a theoretical level, the model can provide insight into personal and organizational characteristics and conversion factors. It can thus provide the key to expanding workers’ capability sets through policies or interventions, and, as a result, increasing the likelihood of sustainable employment. At an organizational level, the model can identify work situations where the capability set – or the achievement of specific functionings – is restricted. Also on the organizational level, managers can evaluate whether the diversity of capabilities is compatible with the aims and ambitions of the organisation. If, for example, in an organization with the aim of being innovative, a considerable number of workers do not consider “developing knowledge and skills” to be a value that is important, managerial attention might be required. The model reflects the complex interactions between individuals and their work context, thus suggesting that polices and interventions should be developed in such a way that they can be adapted to an individual’s particular situation and values. This implies that, on a practical level, the model can provide structure to human resources management (HRM) policy by offering a tool to assess capabilities and by structuring interventions aimed at improving the capability sets of workers. An essential part of this is the joint responsibility of the worker and his/her work context. Workers can be requested to take initiatives and responsibility to develop opportunities / capabilities. The work context should enable workers to develop and maintain their capability set and realize valuable functionings.

From a methodological perspective, qualitative methods in line with Sen’s approach can be useful in terms of identifying the needs of people that should be sustainably employable. It is intriguing to consider conversion factors in this way. Conversion factors are very interesting in terms of explaining gaps in the capability set and can be seen as a focus for interventions. In occupational health practice, most interventions are focused on inputs (eg, task structure and working conditions) and not on conversion factors (eg, HRM, organizational culture and personal attitudes and coping mechanisms).

An additional asset of the CA is the combination of a focus on values alongside a strong “demand-driven” method (particularly the Sen approach of identifying capabilities in the target population). This is in accordance with developments in needs assessment and shared decision-making and is apt for the majority of workers who can actively influence their own work. For the vulnerable group of low-skilled workers, the “Nussbaum approach” might be more appropriate (59). In contrast to Sen, Nussbaum holds that it is possible to construct a list of universal capabilities. This could provide a bottom line by designating a set of basic work capabilities required for “decent work” (60).

Concluding remarks

For present day workers, work needs to add value in order to be sustainable. Assessing values in the sense of a capability set is a good proxy for sustainable employability (6) and a useful addition to existing instruments.

The added value of the CA is that it broadens the scope beyond costs, benefits, and effectiveness (61); it challenges researchers, policy-makers, and practitioners to investigate what is important and valuable for people to achieve in a given (work) context and to ascertain whether people are able and enabled to do so. As such, it is in line with – and stems from – modern economic conceptions developed outside mainstream economic models (62). The capability model challenges researchers, professionals and policy-makers to identify the personal and contextual drivers leading to meaningful employment. Due to its emphasis on values, the CA is able to reflect on the dynamics involved in, and the challenges of, present-day labor markets and work. It depicts a valuable – and obligatory – goal, in this case, a set of capabilities that constitute valuable work and employability, rather than merely describing relationships between variables, as the existing descriptive models often do. Due to this focus on values, the CA can provide direction to current notions of employability and the ICF. It can add to prevailing balance and fit models as well as inform future developments by indicating which aspects of the person–work balance are important, which resources are needed to achieve values and goals, and which aspects of work are rewarding and contribute positively to the sustainable employability of a worker.